This is the last instant to save the oceans. The young generations have to do a much better job than my generation did to curb global warming, cut down on the use of plastics, stop oil spills and cut down overfishing.

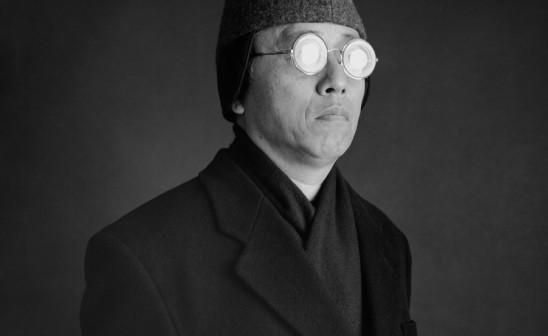

Wayne Levin has probably spent more time than any of us under the surface of our oceans."I’ve been using photography as my primary means of communication for the past 50 years. I’m most known for my black and white underwater work." Born in Los Angeles in 1945, Wayne Levin worked in the U.S navy off the coast of Vietnam in the 1960s, worked with environmentalist and renowned Hawai'i photographer Robert Wenkham in the 1970s, sailed through the Pacific to Australia, shot surfers underwater in the 1980s, did a solo world tour, and eventually turned from a young street photographer to an expert underwater photographer.

Over the years, Levin used his curiosity for life beneath the surface to document the ocean from every angle through analog photography. From dolphins to jelly fish, from tiger sharks to humpback whales and turtles, his shots display an incredible amount of sea creatures. As a witness of ocean pollution, the impact of overfishing, habitat degradation, the destruction of the coral reef, Levin talked us through the current state of our oceans. "The purpose of some of my work is to educate and raise awareness about the ocean, but some of my work is to make people wonder, question their preconceptions of reality," he says. "The ocean is more magical than most people realize."

At the age of 12, your father gave you your very first camera. Did you instantly have a knack for photography?

From the very beginning, I thought I was a great photographer. The more I learned, the more I realized I didn’t know. Also I discovered many other photographers whose work was much more advanced than mine. My family was into racing sailboats. They moved to Hawaii in 1968. So, prior to the Navy, I had a lot of experiences with the ocean. The Navy turned me onto traveling. After my time in the Navy, I sailed through the Pacific to Australia in the late 1960s. From there, I spent a year and a half traveling around the world. A couple years later, I spent 6 months traveling throughout Japan and Korea, and a couple years later, I did a 4-month trip through Mexico and Central America.

Can you tell us more about your sailing trip around the world?

I sailed from Honolulu to Tahiti, through the Society Islands and Cook Islands, Tonga, and Fiji. I left the boat in Fiji and flew to New Zealand. I worked in a tea factory in NZ, then hitch-hiked around both islands. The boat I left in Fiji came to Aukland and I rejoined it. We left Aukland and sailed into a 70-knot storm. We were in the storm for three days and returned to Bay of Islands NZ to repair the boat. Two weeks later, we sailed to Sydney where I met up with an Australian and American guy. We drove up the west coast, across the middle and up to Darwin. I worked in Darwin for a short time, then we went down Western Australia to Perth before hitch-hiking from Perth back to Darwin. Then, we flew to Portuguese Timor and Indonesian Timor. From there, we took a cargo ship through Indonesia to Bali, a ferry to Java and a train to Djakarta. We flew to Singapore, went up both coasts of Malaysia, to Thailand. I went alone to Cambodia and rejoined my friends to Bangkok, then flew to Burma (which had just opened up). Then we flew to Calcutta, took trains all around India and went to Nepal. From India, we went through Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran. From Iran, through Turkey to Bulgaria. By then, I was pretty burned out on traveling, so I went through Europe quickly, flew back to New York, took a bus across the US, and I went back to Hawaii. This is the short summary of that trip.

Would you have a memory from this solo world tour you’d like to share with us?

I left my friends who wanted to stay in Thailand and I went alone to Cambodia. At that time, Nom Penh was a paradise, a beautiful city on the Mekong River. There was a mixture of Asian and French atmosphere, with lots of sidewalk cafes. I stayed at a pagoda, the priests and some teachers would take me out to dinner to practice their English. I realize that under Pol Pot, they were probably all killed, as being able to speak english was punishable by death. Then, I went to Angkor and rented a bike, spending 3 days touring all the ruins. They were amazing. As this was before Cambodia got sucked into the Viet Nam war, the ruins were more pristine than they are now, and Nom Penh will never be the way it was when I visited it in 1969.

In the 1990s, you landed to Kona island, Hawaii. Can you describe this place for us?

We live in South Kona, which is quite rural, very lush and green. There are two major drawbacks. The first is the vog (volcanic smog), which has been a problem for the past 30 years. It reached new heights during the recent big eruption. But since the eruption, it has gotten much better. The other problems is Coqui Frogs. They are little frogs, introduced less than 15 years ago to Hawaii from Central America. The Coqui population has exploded on Hawaii Island. They produce a very high pitched sound that can drive people crazy. Fortunately I’m hard of hearing, so all I have to do is remove my hearing aid and the noise disappears. Moving to Kona was my first underwater encounter with marine mammals. I had close encounters from above water earlier in California. I remember a time when we were sailing and we almost hit a surfacing Gray Whale. The waters are full of life, colorful reef fish, dolphins, rays, and until 2015, beautiful reef. But tragically in the fall of 2015 we had a coral bleaching event which killed over 50% of Kona’s Corals (cf: "Beneath The Surface" in the last question).

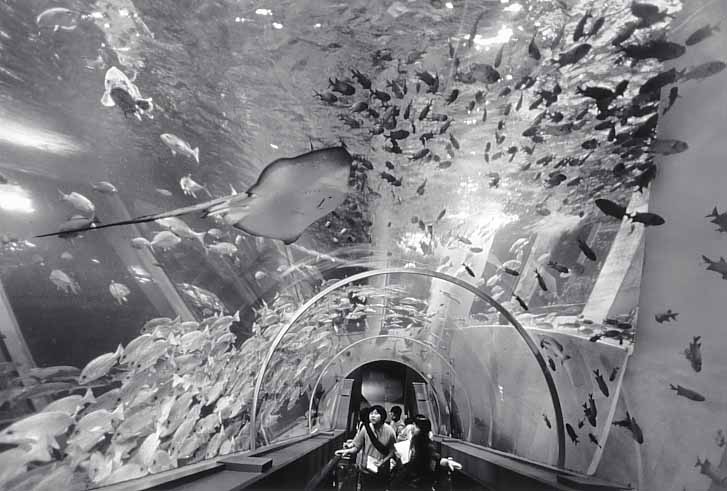

You created an interesting series of pictures of aquariums in the US and Japan, to, I quote, « investigate the phenomena of society creating hi-tech mini oceans as the world’s oceans become increasingly endangered. » Can you tell us more about the book you published in 2001 entitled « Other Oceans »?

"Other Oceans" was a book that had two short sections of Ocean images, with a long section of images shot in aquariums., mostly taken on the West Coast of the United States (California), Hawaii and Japan. I have mixed feelings about aquariums. I really enjoy seeing them and photographing them. They also do educate people about the ocean and, hopefully, encourage them to be more aware to the threat to the sea. On the other hand, they act as a kind of high-tech substitute that can replace the experience of the real ocean. Also, before being an underwater photographer, I was a street photographer. For me, street photography was not only about timing, but also about visual complexity. The aquarium work allowed me to get back into some of the things I loved about street photography: Breaking the photograph into as many pieces as possible, pictures within pictures, reflections and refractions…

You probably spent more time than any of us under the surface of our oceans. Over time, have you witnessed a change regarding the oceans?

I totally respect the ocean. I realize that every time I enter the ocean, I’m putting my life into an entity that is far more powerful that me. It also makes me feel good to be in the ocean, it calms me, and puts my life in perspective. To me, the biggest change that I noticed has been the destruction of the coral reef. Many people in Kona say that the reef fish populations are down from what they used to be. I’m not really aware of that. It seems like there’s still lots of reef fish. I think there’s less top predators. I see less sharks than I used to see. Yes, the water temperatures are noticeably warmer.

You have a solid reputation as a black and white underwater photographer. What would be your message to the next generation and to the world concerning our oceans?

I think this is the last instant (if it’s not already too late) to save the oceans. They have to do a much better job than my generation did to curb global warming, cut down on the use of plastics, and other pollutants that find their way to the sea, stop oil spills, cut down overfishing, and in general, be willing to give up some of our short term comforts for long term survival.

Would you describe yourself as an activist? If so, would you say you tend to use your art to raise awareness of the ocean?

When I was young, I was an activist, but through much of my life, I was not so much. However, now I am once again an activist because of the current political situation in the US and worldwide. The purpose of some of my work is to educate and raise awareness about the ocean, but some of my work is to make people wonder and question their preconceptions of reality. The ocean is more magical than most people realize.

I’m not sure if showing the beauty of the world with art really is effective in moving people to protect that beauty. If you put a beautiful picture on the wall, it might encourage you to protect that beauty on the earth, but it might also become a substitute for that beauty. Kind of like how aquariums become substitute oceans. On the other hand, showing ugliness may not work either. Susan Sontag wrote a book called « On Photography ». She had a chapter about war photography. Her view was that most war photographers want to show people the brutality of war and make them realize how horrible war is. In reality, the abundance of war photography end up anesthetizing people to the brutality of war.

Why did you choose to stick to black and white photography to document the underwater world?

I first seriously got into underwater photography in the early 80’s when I decided to photograph surfers underwater. I first tried color but everything came out blue and murky. When I switched to B&W, I was able not only to control the contrast, but it added ambivalence to the images. You couldn’t be sure if the surfers were diving under breaking waves or flying through clouds. Also, I had a lot more expertise with B&W than with color. I decided to stick with B&W which became a large part of what I’m known for. I also stuck with film photography, even though I second guess myself every time I run out of film and something amazing happens.

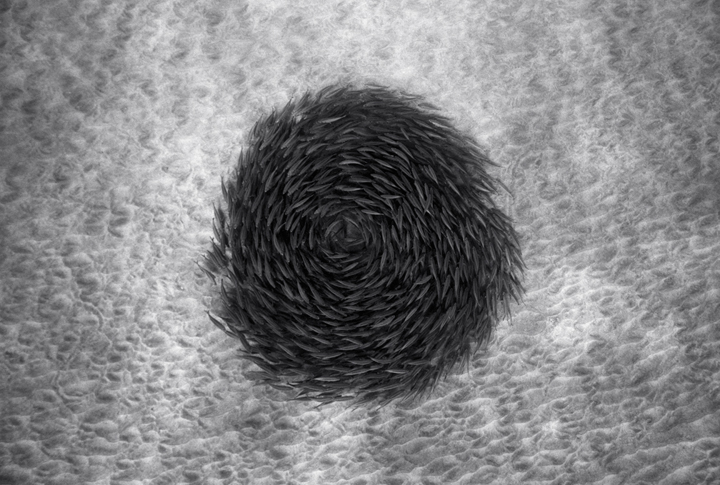

Dolphins, jelly fish, white sharks, tiger sharks, akule, humpback whales, turtles, sea lions… Do you have a favorite sea creature?

I think my favorite subject are large fish schools. The shapes they make and their movement are amazing. I love watching the shapes and changes of the schools, especially when they interact with predators. The coordination and unity of the schooling fish make me wonder what is the individual. Is it the individual fish, or is it the school, with the individual fish acting like cells within a larger organism?

What has been your most intense and vivid memory beneath the surface?

It’s really hard to say, there’s been so many. So I will describe a recent one when I dove at a spot where you sometimes encounter Tiger Sharks. As I was headed out along a boat channel, a big tiger passed me on the other side of the channel. It was at least 14 feet but wasn’t very close to me. I swam south along the drop off at a depth of about 70 feet. I decided to follow the drop off until I had 1500 pounds of air, and then turned inshore and went back in shallower water. As I was about to go inshore, I saw a large tiger shark 30 feet above me also swimming inshore. As I got in shallower water, the shark was swimming parallel to me about 20 feet away. I’d guess it was a 12-foot shark. Then, from behind me, a larger tiger (about 14 feet) came straight at me. She passed right over my head, within touching distance. Then the other one circled and passed me also within a couple feet. The two sharks kept making very close passes, sometimes along my side and sometimes over my head. I had to constantly look in all directions because I didn’t know where they would come from. Though it made me a little nervous, I felt fairly safe as I was on scuba and I was staying right against the bottom. I wouldn’t have liked to be in that situation snorkeling on the surface, with the water column below me. I went in within viewing distance of the rocky shoreline, in 15 feet of water and they were still coming at me. Finally, as I swam further north, they finally left me. I felt it was an amazing encounter.

Over the years, you published some impressive books, you held incredible exhibitions, you’ve been awarded many times and you’ve been a teacher. What are you the most proud of so far?

It may have been a show of my work at the Dimbola Museum, on the Isle of Wight off the south coast of England. The Dimbola Museum was the home of the renowned English photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who photographed in the mid-1800’s. I felt very honored to show at Julia Margaret Cameron’s home. Also I was very proud of my Akule show at the National Academy of Sciences, in Washington DC. The Washington City Paper named it the best photography show of 2015 in Washington DC. There were a lot of other amazing shows there that year.

Tell us more about your exhibition « Beneath the Surface » in September 2018.

Diving in early September 2015, I was surrounded by Kona's beautiful coral reefs. By mid October, I was shocked by what I saw: Absolute devastation caused by a severe El Nino and climate change. The water temperatures were upward of 85 degrees (Kona's water temperatures usually peak at about 80 degrees). Much of our coral had been bleached bright white. The Cauliflower, Mounding, and Plate corals seemed to have taken the hardest hit. There is a stark beauty to this Ghost Coral, but the reality is not beautiful at all. While there was hope that the bleached coral would recover once the water temperatures cooled, the majority of bleached coral did not. In the bleaching event of Fall 2015 through Winter 2016, over 50% of Kona's corals perished. For me, this was a first hand experience of the devastation caused by climate change. So to those with doubt, I assure you that this devastation is real. I realize many people don't pay too much attention to what happens beneath our ocean's surface, but if we are going to save the ocean we have to act now. If the ocean dies, so will humanity. This work is in three parts: Beautiful healthy coral prior to the 2015 bleaching event; Bleached coral during the 2015 bleaching event; Dead and algae covered coral after the 2015 bleaching event.

More infos about Wayne Levin on his website.