I remember the very first time I saw an orca. I was standing on a SUP and an orca just went close to me. The dorsal fin was about 2 meters. Way taller than me. The orcas itself is 3-4 times bigger than its fin. Very impressive!

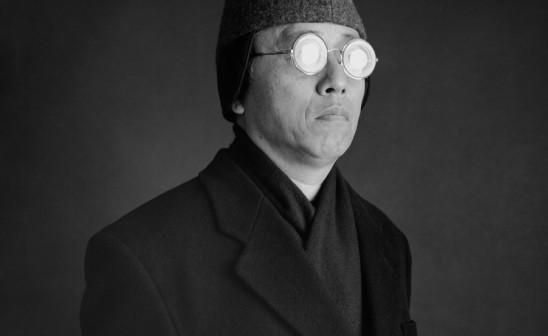

Known as a scientist, an expert in acoustics and a nature lover, Jorg Rychen managed to combine his passion for science and for nature. Working as a researcher and a lifeguard, Jorg is definitely not your typical scientist. He focused his work on neurophysiology research on freely behaving animals and managed to spend his spare time in wilderness, both as a freediver, a ballooner and farmer.

In last December, he joined our Panthalassa crew members on our latest expedition up to Tromsø, Norway. The expedition was above all about the journey of a group of adventurers meant to record and understand the secret language of the Orca Killer Whales, described as the most intelligent creatures on earth. We spent a few days with Jorg on a small size boat under below-freezing temperatures, sharing one of the most spectacular visions which is witnessing orcas in their natural environment.

Hi Jorg, can you tell us a bit about your background?

I studied experimental physics, I obtained my PhD at the ETH Zurich for studies of quantum phenomena in semiconductors. Then, I founded a company that provides scanning probe microscopes all around the world. I sold the company in 2008 because, even though it’s very interesting, everybody in physics is a little bit of a nerd and it remains an all-male environment. To be honest, it’s socially boring. Today, I split my time between my lab and the shore of a lake since I’m also a lifeguard during summer in Zurich. As a lifeguard, you’re in the sun, you feel the wind, you see the clouds, you have a lot of friends and people around you. This job is basically at the very opposite of being a lab technician. I’m also employed at the Institute of Neuroinformatics where I work as as Prof. Hahnloser research group. My interest is to solve automation, measurement, and instrumentation problems arising both in neurophysiology research on freely behaving animals and in anatomy work using high-throughout electron microscopy. I work with a lot of mathematicians, physicians, and biologists used to do a lot of experiments with song birds. Working with them, I would record all the songbirds. Songbirds are a model for basic research and provide ideal signals for study and experiments. Birds are a model animal in neuroresearchs, as process happen in the brain. Only birds, bats and dolphins can do that That's why it would be interesting to learn more about orcas.

Where does your fascination for the orcas and, more widely, for freediving come from?

I’d probably need to tell you the full story. My father was a mountain guide in Switzerland. When I was a kid, we did a lot of adventures in the mountains. And I remember that, even as a child, I could hold my breathe longer than anyone else. I guess it’s just something that’s given to you somehow. So, since a young age, I’ve been very good at freediving. I remember being on holidays and seeing Russian girls with wetsuits diving down deep in the water. They told me « this is freediving, it’s an old sport . » It was around 1999, and I was hooked. However, freediving is all about numbers. It’s all about how deep you can go, how far you can swim, and how long you can hold your breathe. I’ve never been very interested in this competitive side of freediving. For me, freediving is more about freedom. I like the fact that you don’t need a lot of equipment; just your mouth, the mask, and fins. It’s the same with climbing. I prefer bouldering these days because what you need is just a pair of shoes. This is everything I love. Going back to freediving, when you dive down, you’re overwhelmed by this really strong silence. I think it also has to do with the ears, it makes this feeling of complete silence. You can also hear the orcas from far away. It’s just a beautiful sound. I first met Jacques (De Vos) a few years ago, he was my freediving instructor. I remember the first time I saw an orca. I was standing on a stand up paddle and the orca just went close to me. The dorsal fin was about 2 meters high, so taller than me. The orca itself was 3-4 times bigger than its fin. Orcas are really big, especially when they come close to you. It was very impressive so, at that time, what I had in mind was to study the orcas the same way I study songbirds. One experimental method to decode the 'neural algorithms' underlying song learning is to record the song of a bird with a microphone and interact with the bird via a loudspeaker.

The December expedition aimed at decoding the secret orcas communication. From your scientific point of you, why is it so interesting and so important?

There are several aspects. One aspect is the scientific side of the expedition which is basically the information approach. Obviously, orcas are able to exchange some information and perform conversations. For example, when orcas hunt, they agree on a hunting strategy beforehand. During the hunt, orcas remain silent. It means every individual agreed and organized their hunt before. They are somehow able to discuss what to do together. I wouldn’t call it a language yet - in the terms of a subject, verb, and complement - but it’s interesting to see how orcas are sharing information. Orcas’ ears are their primary sense, while for human, it’s the eye. Orcas rely on sound production and also see with the ear, using their sonar. They use the vocalization to see, but they also use the vocalization to communicate. For us, the two are separate, we have the eye and the ear. Orcas navigate by echolocation, and the clicks and whistles are part of the orca’ sonar. I think it’s an interesting thing to study.

How did you proceed to try to start decoding orcas language?

It’s always a bit of a problem because we’re used to make just small announcement. We put the hydrophones underwater and recorded the orcas. The most challenging part was to separate individual vocalizations from the background noise and from the other orcas. This is a difficult part because, at the end, we want to come up with one single track of a single orca. Orcas are known to have three kind of vocalizations: clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls. So the idea is to analyze the single track and see which orcas is responding to which one. The collected data creates statistics. Analysing data, we’ll be able to understand who is talking to who. The objective is to study whistles in order to make a catalog of whistles and analyze how often they are repeated. Doing so, we’ll be able to make a vocabulary, a kind of protocole, and learn how they discuss. For example, science have studied bats for a long time. Because of their near blindness, bats use vocal signals - echolocation - to communicate, they are easier to study. As sound goes everywhere, they somehow steal the echo of another bat and use sound wave for communication. They echolocate within specific frequency ranges, and I think it’s the same for the orcas. The questions is « what kind of frequency do orcas have? » Last year, I made some recordings and it was interesting to see that they recently found a frequency. Orcas can basically tickle another orcas remotely. It means there’s maybe a physical interaction over a long distance.

What do you expect from the data collected during The Sound of Intelligence expedition?

We’ll gonna analyze it in order to create a vocabulary and statistics. We’ll start classifying the produced sound and test in playback experiments. It’s a good idea to try to create interactions with them. For example, we’ll maybe find out that orcas have a signature call, like a name! If we have a collection of signature whistles, we can maybe compose another new signature whistle, then restart playing back and then the orca can recognize the sound. That would be awesome!

The December expedition took place in a remote fjord north Norway, above the arctic circle. What was the most challenging part of it all?

What I found out is that the most challenging part is always to handle the materials, for many reasons. It is very cold, you are in a wetsuit, everything is wet, cold and dark, and you wear gloves. So everything is tough and you need to be sure it works. I tried the same experiment last year so I gained a lot of insights regarding the handling of products. For this expedition, I built up a container to put the records, and did a test in the lake of Zurich.

When you’re not in your labo, what do you do exactly?

I’m also a balloon pilot. Since I’m a child, I have this passion for airships. I’ve always wanted to build an airship but to do so, you first have to have a licence for ballooning. So I started ballooning a few years ago. My goal is still to own a human-power airship, that looks exactly like an orca by the way! I’m a member of a ballooning club and we co-own two balloons. I also have a small farm in the mountain in Switzerland where I grow herbs and spices. You have to climb up there, it’s a very steep region but I like that. I like to have a cool project in mind, something that gives me a focus.

Portraits : Pierre David

Orcas photos : Jacques De Vos