When fish stocks plummeted due to increased salinity, the surrounding fishing villages found themselves hungry and jobless.

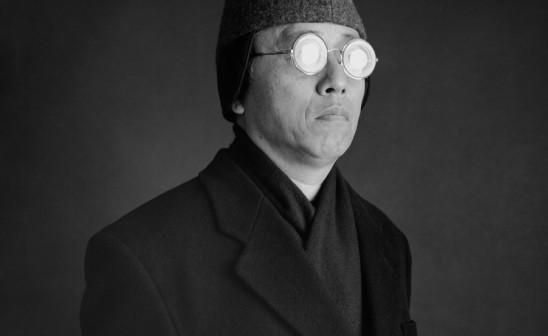

Currently based in Chiang Mai, Thailand, award-winning documentary photographer Taylor Weidman’s work focus on the effects of modernization and human rights issues.« Riding in -20°C weather with Mongolia’s reindeer herders, diving with Thailand’s sea gypsies, and photographing Kazakh ice fishermen were all unforgettable experiences. » After spending two months in Central Asia between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, Weidman produced a long-term series of pictures for National Geographic about the Aral Sea, considered the world’s fourth-largest freshwater lake decades ago. However, in the 1950s, the lake became the victim of the Soviet Union’s agricultural policies. Water was intentionally diverted causing a massive ecological disaster.

Today, thanks to large-scale restoration efforts, the Aral sea have seen a resurgence of fish. Fish catch in the North Aral Sea has grown six-fold since 2006, bringing commerce back to the inland town of Aralsk, Kazakhstan. « The Korkoral Dam surpassed all expectations, leading to an 11 foot increase in water levels in just seven months. Today, fishermen say 15 different species of fish have returned to the sea. » We wanted to learn more about the situation and the fishermen community photographer Weidman met during his journey.

Currently based in Chiang Mai, Thailand, what do your surrounding look like?

Chiang Mai is a beautiful, small city in northern Thailand. The city is known as the ‘jewel of the north’ and has a vibrant arts scene and cafe culture. It’s very relaxed and is surrounded by hills, jungles, and waterfalls, which make for fun hikes or motorbike excursions on weekends and holidays.

Working for important medias like The Wall Street Journal, BBC and CNN, what have been your most vivid memory as a photojournalist?

As a photojournalist, I have opportunities to travel and see things that I would never be able to in any other line of work. Riding in -20°C weather with Mongolia’s reindeer herders, diving with Thailand’s sea gypsies, and photographing Kazakh ice fishermen were all unforgettable experiences.

You recently produced a long-term report about the Aral Sea for National Geographic. What did bring you to Kazakhstan?

I spent 2 months in Central Asia between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. I’ve been to Mongolia nearly a dozen times, where the country’s Soviet past and the rise of nearby China make for a fascinating landscape to work in. I’d always wanted to go to Kazakhstan and other countries in Central Asia since they face a similar situation and coverage from these areas is scarce.

In 1957, the Aral Sea produced more than 48,000 tons of fish. However, in the 1950s, water was intentionally diverted causing a rise in salinity and the death of freshwater fish species. What has been the impact on the fishing industry and fishermen community?

The Aral Sea, straddling Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was once the fourth largest freshwater lake in the world. But by the 1990s it was a shrunken ruin, thanks to Soviet policies that diverted water for agricultural purposes from the lake's two river sources. When fish stocks plummeted due to increased salinity, the surrounding fishing villages found themselves hungry and jobless; many residents left in search of better opportunities. For example, in Tastubek, a fishing village on the Aral Sea, so many of the fishermen left that there were only 9 households remaining.

Today, the lake is said to be a tenth of its original size. What does the lake look like today?

You can see from satellite images that the Aral Sea on the Uzbek side is a sliver of its former self. The lake dries more and more each year and the remaining water is too salty for fish to survive. I had the chance to visit the former fishing port of Moynaq in Uzbekistan. Here you can see lines of boats rusting on the former sea bed, although the shores of what remains of the Aral Sea are now around 150km away. When the fish disappeared, everyone engaged in the fishing industry had to search for new jobs. Today, the economy is mostly reliant on seasonal remittance work in Russia.

Despite the disaster, in 2005 a dam was constructed to help Kazakhstan’s North Aral Sea’s fate. Tell us more about this revolutionary project.

Financed by the World Bank, an eight-mile dam was constructed in 2005 on the Kazakh side of the Aral Sea, just south of the Syr Darya River. The Korkoral Dam surpassed all expectations, leading to an 11 foot increase in water levels in just seven months. Today, fishermen say 15 different species of fish have returned to the sea.

Did this project bring optimism and hope to the community?

Absolutely. Many of the former fishermen were able to go back to their jobs and are again earning a good income. Local fishing communities were shrinking, but now are again growing. Tastubek, the fishing village I mentioned that shrunk down to just 9 households, now has 34.

You met a local fisherman named Omirserik Ibragimov. Tell us more about this man, his daily life and fishing habits today…

Omirserik was a fun, brash 25-year-old who lived in a fishing village called Tastubek. He fished each day with his father, Kiderbai. During the winter, the two men would ride out on the ice in Russian jeeps where they would drill holes in the ice and hang nets below the ice, then come back a few days later to collect the fish.

To what extent is the sea the source of life for the community?

Fishing communities like Tastubek continued to exist after the fish died off because they also kept camels. However, it was difficult to make ends meet and many residents left the village. Now that the fish are back, the communities are again growing since fishing provides a solid income for families.

This recent prosperity surprisingly generated negative consequences like illegal fishing. Tell us more about that…

This was one of the most surprising revelations we found. I had assumed that local residents, after experiencing firsthand the vulnerability of the fishing ecosystem, would be motivated to safeguard the fish stocks. Unfortunately, instead we learned that fishermen were trying ignoring long-term harm by chasing short-term profits and it was common for today’s fishermen to use illegal fishing methods - employing nets that are cheap and easily torn/lost and fishing during the breeding season.

As a photojournalist, you’re a witness of the ecological situation. What would be your message for the future generations?

My message would be for this generation to think about the environmental legacy they are leaving for future generations. Over and over, I see unsustainable, yet extremely common practices decimating fish stocks, clear cutting rainforest, polluting the air and water, and abusing the environment in myriad other ways. Environmental regulation, where it exists, is often undercut by corruption. We need to ask ourselves what kind of a world we want our children to grow up in and work together to build that future.

What are your next projects?

Throughout Southeast and Central Asia, China is an increasingly powerful actor, and I think my next project will concentrate on China’s ambitious One Belt One Road plan as it builds infrastructure and exerts influence throughout the region.

Discover more of Taylor Weidman's work on his website.